Most businesses use the default settings from their accounting system which usually causes the gross margin to be reported too high. This causes profit leaks due to mistakenly under-quoting, over-spending on sales promotions and mistakes about understanding the true profit of different customers. This is one of the easiest mistakes to repair. A few simple tweaks is all it takes to fix the problem by moving to a correct margin.

This article discusses correctly identifying variable costs, and how to get contribution margin from your accounting system, be it MYOB, Saasu, Xero or QuickBooks.

Part of GrowthPath's Profit Engineering Essential Skills series

Your gross margin is a crucial business number because it tells you the true benefit of a sale. Knowing your margin lets you make decisions on discounting, quotes, special deals, competitor response and whether investments in marketing are worthwhile. The traditional definition of the "gross margin" is an old-fashioned short-cut that sacrifices accuracy. It has the sole advantage of being standardised across businesses, but the law of the lowest common denominator applies. In virtually every business, it provides incomplete information. Since it ignores variable costs other than stock, it distorts the margin. Most small and medium sized accounting systems make it easy to fix.

Cash vs Profit

In this article, we assume you take a profit point of view, not a cash point of view. The profit point of view (also known as accrual accounting) is a superior system for measuring performance and for keeping on top of future cash flows, such as who owes you money. You may like to read Cash vs Profit if you are unclear why that is so.

Gross Margin and the cost of goods sold

For trading businesses, inventory is a big component of the cost of a sale. When it comes to inventory, the "profit" method records a cost when you ship an item to a customer. The cash method records the cost when you pay your supplier. This can be a big timing difference: imagine the stock sits around unsold for three months. For the typical trading business, the profit method provides more accurate results than the cash method because it matches expenses and sales more closely to real-world events. A business incurs the cost of replacing stock only when it sells stock, and this is the timing that the profit method uses.

The traditional gross margin method includes the cost of sales in its calculation. In fact, the traditional gross margin only reflects the cost of sales. It ignores other variable costs. Have a look at the expenses in your Profit & Loss report to see what I mean.

There are two methods for working out the value of inventory sold: Perpetual and Periodic. If you see an account called "Purchases" in your gross margin, your business is using the inferior Periodic method. You can read more about which inventory method to choose (the article also covers some of questions about how to cost your inventory).

Whichever method you use, the idea is to recognise the cost of inventory when it is sold. This cost is called the "Cost of Goods Sold".

Since you must replace this stock in order to meet the next sale, the money you earn from the sale is not entirely all yours to keep. The "true" value of the sale must deduct the replacement cost of the stock. This "true" value is called "Gross Margin".

Breakeven

So if we run a cafe and we sell black coffee in take away cups, each sold cup of coffee causes us to replace a $0.10 cup and $0.50 cents of coffee.

If I sell it for $3.50 (ignore GST and other taxes), I have to take $0.60 and reserve it to replace stock. The sale really gives me $2.90 to play with. THe $0.60 is the cost of goods sold, and the gross margin is $2.90. If I have $10,000 of rent, wages and other "overhead" costs per month, then each coffee gives me $2.90 to contribute to covering those costs. In this case, I need to sell $10,000 / $2.90 = 3449 cups each month. This is the breakeven.

After that point, each additional coffee sold increases my profit by $2.90.

Margin Percentages

Instead of remembering the margin as $2.90, we can express it as a percentage of sales. In this case, the gross margin percentage is $2.90 / $3.50 = 83%. This means we get to keep 83 cents for every dollar sold.

GST arithmetic, and why we ignore GST in our sales figure

GST is Australian for VAT. When a business pays GST, the Tax Office expect you to remit to it 10% of each dollar of sales. It's easiest to add this to sales, so while we treat the coffee as being worth $3.50 of revenue, we must actually ask the customer to pay $3.85. We then give the ATO $0.35. It turns out that adding 10% to sales is the same as deducting 1/11 from the "GST Inclusive amount". The customers pays $3.85. One 11th of that is for the ATO, leaving $3.50 as a sale.

Cash accounting methods treat $3.85 as the sale. Profit methods treat $3.50 as the sale. We prefer the second. So the gross margin percentage ignores the GST component. The result would be the same regardless of whether a business is GST registered or not.

Naturally, we also ignore the GST part of our expenses, to be consistent. The accounting system does this for us.

The link between costs and sales

If a business has a gross margin of 50%, each dollar of sales is worth $0.50. This means that if you increase your marketing spend by $100, you need $200 of sales to cover the cost. If you lose $100 of sales, you need to cut cost by $50 to cover it. If you cut costs by $500, you have achieved the same profit boosts as a $1000 increase is sales.

One dollar of overhead costs is the same as $1 / gross margin percentage.

So a business with 80% gross margin which faces a $500 increase is costs needs to make an extra $500 / 0.8 = $625 of sales.

Variable Costs and overhead costs

The big problem with the traditional gross margin is that the logic is sound, but it is not complete. There are other costs that you only incur as a consequence of a sale. These are known as variable costs. This is a subtly misleading term. We don't mean costs which go up and down over time; we mean costs which change directly because you sold something. Variable costs are also known as direct costs: direct because they are driven directly by executing a sale. Variable costs don't happen when sales don't happen.

Costs which are not "variable" are called "overhead" costs. Sometimes you hear the term "fixed costs" for overhead. But many overheads are not actually fixed. Rent is usually a fixed overhead cost, but a business electricity bill is an overhead costs which is not constant. Overhead costs are costs the business is committed to, regardless of whether a sale is achieved

What is the time horizon to determine if a cost is variable or overhead?

It's hard to find this answer in the text books. Our rule is that time frame should be linked to the decision process and commitment of your typical customer.

If, for example, you are selling directly to consumers, the commitment by the consumer is usually very short. Perhaps you sell chocolate biscuits online. You may invest a lot of money in machinery to make and package chocolate biscuits, and this machinery may have a life of ten years. But consumers don't plan this purchase in advance. They make very short term decisions. So only the most short term costs are your variable costs: typically the cost of ingredients, packaging, outbound transport. You may have made long term bets by buying machinery, but these costs are your committed costs; they are overheads.

On the other hand, if you are making submarines, with a twenty year sales contract, things are very different. Virtually every significant cost is only committed to after you win the tender. In this case, most costs are variable, because the decision timeframe of the customer is very long.

Note that the decision to make costs short term (by using sub-contractors and other flexible arrangements) or the decision to make costs overheads, by making investments in long-lived assets, is separate to this decision making time-frame. This cuts to the question of the how you decide which risks to take on, and which to avoid, which will be covered in a later blog.

A simple example

An online business selling t-shirts has inventory as a variable costs. It also has outbound postage.

The postage cost is not treated as a "cost of goods sold" in the traditional model, and it is left out of the gross margin, which is a mistake.

Correctly gathering all variable costs leads to the "contribution margin", which is simply a more inclusive and accurate version of the gross margin. The traditional gross margin leaves out variable costs other that cost of stock, which means it overstates margin. This can lead to incorrect decisions about discounting, and paybacks for marketing programs which are too low (meaning you can lose money by surprise).

When is a cost "variable"?

A cost is "variable" when there is a strong link to its being caused by selling something, and when it is big enough to justify worrying about.

So the cafe may believe that the cost of little wooden stirring sticks, and sugar, is variable, but when it comes down to the value involved, it's too small. Likewise, the coffee requires electricity to heat the water, but the amount per cup is miniscule. We probably leave all of these costs as overheads.

The cost of coffee beans is too important to be left as an overhead for a cafe. However, an airline serving coffee to passengers would not track coffee as a variable cost.

Other typical variable costs are sales commissions, subcontract labor, packaging, outbound freight, venue or facilities hire matched to a specific event for which you've sold tickets, books and kits handed to customers.

The advantages of contribution margin

We saw above some uses of gross margin: in calculating breakeven, and the sales needed to justify an investment in marketing.

These are only accurate if you have include all variable costs. For example, a business which sells sunglasses online with free shipping may have a cost of goods sold of $30, for the purchase cost. The sunglasses sell for $59. We will ignore GST completely (there isn't GST on sunglasses any way).

This is a gross margin of $29.

If such a business decided to spend $1000 on a Google adwords campaign, it would conclude that we need to sell 1000 / 29 = 35 sunglasses to break even, which is a sales value of 35 * $59 = $2065

But this is wrong, because we have postage and packaging costs of $10 each time we sell. The contribution margin includes all variable costs, so it is $59 - ($30 + $10) = $19. We actually need to sell 53 sunglasses (or $3127)

Fixing your accounting system

The organisation of your accounts is called the Chart of Accounts. The "Chart" names your accounts, and groups them. A sophisticated system may group superannuation and wage costs together into "Employment Costs", so you get a subtotal.

The Gross Margin is simply sales - the total of variable costs. The default Chart of Accounts always contains "Cost of Goods Sold", which is the replacement cost of inventory you sell.

They usually never include other variable costs.

So you need to change you Chart of Accounts to make sure that

a) each variable cost has its own account

b) these accounts are grouped to be in the gross margin.

Given Variable Costs their own account

Most accounting systems have an account called "Postage" or "Postage and Freight". The typical business sending items to customers has outbound freight, and inbound freight (paying someone to deliver goods to a warehouse, for example). The outbound freight/postage is often a variable costs, as in the T-Shirt retailer. In this case, you need to create separate inbound and outbound accounts, and put the outbound account in the Cost of Goods Sold group.

Another typical variable costs is commission paid to win sales. You probably have such an account. As long as it records only commission which is varies with your sales, you need to move it into your margin.

Moving Variable Cost Accounts into the Margin

This depends on your accounting system. In MYOB, the account numbering determines where it appears.

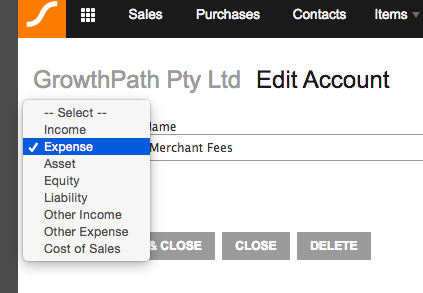

In Saasu, it's easier: you go to View->Accounts, edit the account and put it in Cost of Sales.

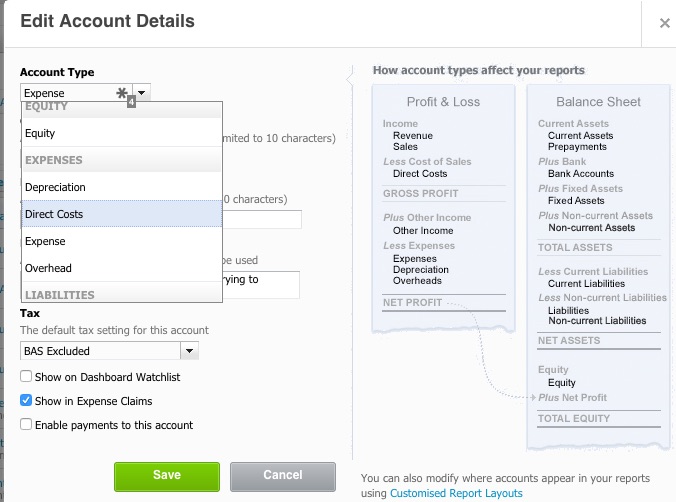

Xero has a flexible report editor that lets you put accounts or groups of accounts into the gross margin. At the moment, this is probably the most sophisticated P&L of the entry level accounting systems.

In Saasu, edit the account and change its type to Cost of Sales. This moves it into the margin.

In Xero, edit the account and change its type to Direct Cost. This moves it into the margin.

The process is virtually identical in all accounting sytems. MYOB is little different because the position of an account in the hierarch is linked to its account number. Most other systems are more flexible.

So in MYOB you may be looking at creating a new account, journalling balances into it, and deactivating an old account.

Profit from your new P&L

Your P&L still reports "Gross Margin", but it is more accurate. If you can change the name of the Gross Margin summary to be Contribution Margin, do so.

Case studies in using the Contribution Margin for decision making will come in a later blog post.